Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

‘Satanic ritual abuse’ in Sodom? Of course!

Oct. 7, 2015

Oct. 7, 2015

“Sodom Laurel was first named Revere, and is still Revere on topographical maps, but I seldom hear anyone call it anything but Sodom. (Madison County native Dellie Norton said) she had heard that years ago, when logging first came to the region, there were numerous logging camps and a lot of men away from home, with money and time on their hands. Violence and promiscuity were rampant. Dellie had heard that a preacher, upon arriving in Revere and having seen the residents firsthand, remarked ‘You people are just like a bunch of Sodomites.’ The name stuck.

“Lately, partly for religious reasons and, of course, the negative connotations of the name Sodom, some community members have started using the name Revere again…. But also times have changed – the community is quieter than it used to be – Revere seems a more apt description of the place.”

– From “Sodom Laurel Album” by Rob Amberg (2002)

I guess it fits that a defendant unfortunate enough to be charged with “satanic ritual abuse” would also be unfortunate enough to have his hometown known as Sodom – a coincidence surely snickered about in the culturally hostile courtroom in Asheville where Junior Chandler was convicted.

Coincidentally, the district attorney in a Hendersonville ritual abuse prosecution infamously ranted about Michael Alan Parker’s having resided in “Sodom and Saluda.” (The jury bought his Bible-pounding, but Saludans weren’t pleased.)

McMartin Preschool acquittal did little to stem spread of hysteria

Andersen

May 18, 2018

“Despite the acquittal in [the McMartin Preschool case], the hysteria kept raging there and nationally; mainstream news still gave it credence, police still made arrests, prosecutors still prosecuted, and true believers among psychologists and psychiatrists (and their clients) still believed and proselytized, often with a government imprimatur….

“In a small town in Tidewater North Carolina, children testified that a satanic cult operating a day care center had ritually abused them – and taken them in hot-air balloons to outer space and on a boat into the Atlantic where newborns were fed to sharks; several people were sentenced to long prison terms and served time before their convictions were overturned or charges dismissed.”

– From “Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History” by Kurt Andersen (2017)

The ripples from McMartin were even more pronounced in Edenton, after prosecutors brought back from California a crucial lesson: Conceal, obscure or destroy the therapists’ notes that would reveal how relentlessly the child-witnesses had been manipulated.

![]()

Why the panic ‘needs to be remembered’

April 22, 2013

April 22, 2013

“Lecturing recently, I mentioned the American witch-hunts of the 1980s and 1990s. When the audience looked puzzled, I explained that I was referring to the Satanic Panic of those years, the wave of false charges concerning ritual child abuse and devil cults that made regular headlines in the decade after 1984. The explanation helped little.

“Even people who had lived through those years, who had been following the media closely, had precisely no recollection. Lost in memory it may be, but the Satanic Panic needs to be remembered, if only to prevent a renewed outbreak of this horrible farrago. And when better than in the 30th anniversary of the affair’s beginning?

“It all started in southern California, in Manhattan Beach, in the Fall of 1983….”

– From “Remember the Satanic Panic” (Jan. 9, 2013) by Philip Jenkins, Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University, on Real Clear Religion

I share Dr. Jenkins’ concern about public memory, of course.

Which are more worrisome – those who have no recollection at all of cases such as McMartin and Little Rascals, or those who have forgotten they all were hoaxes?

‘Most people thought I had lost my damn mind’

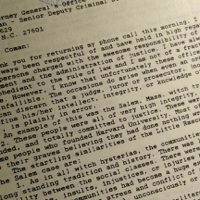

Portion of Dee Swain’s Jan. 12, 1993 letter to Attorney General’s Office on “the startling similarities of the Little Rascals case and the Salem” witch trials of 1692-93.

April 5, 2016

At a time when the Little Rascals claims were exposing widespread gullibility, a gritty band of doubters – e.g., Raymond Lawrence, Glenn Lancaster, Jane Duffield, Doug Wiik, Susan Corbett and Dee Swain – was desperately working to keep the defendants from being crushed by public opinion and prosecutorial coercion.

As treasurer for the Committee to Support the Edenton Seven, Swain distributed donations to defendants, facilitated the lowering of Scott Privott’s exorbitant bond and wrote an epic four-page (single-spaced!) letter educating the attorney general’s office on the errors of its ways.

How was it that a propane dealer in Washington, N.C., could see through the fog that engulfed so many professionals?

“It was obvious to me right away that it was hysteria,” he says. “I didn’t get involved until after (Bob Kelly’s) conviction – I had thought surely the jury would see through it….

“I’ve always been a skeptical person, someone who stands outside the box…. Most people thought I had lost my damn mind, defending ‘child molesters’…. I got anonymous phone calls….”

Swain is surprisingly generous to those who bought into the “satanic ritual abuse” stories elicited by prosecution therapists: “There aren’t any villains. They all acted in good faith. They were on a mission. They were going to be heroes….. You could see it all in ‘Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds’ (by Charles Mackay, 1841).”

And why does he think none have stepped forward a quarter century later to recant? “What they did was too terrible to admit to themselves.”

![]()

0 CommentsComment on Facebook